Blog

-

News

Before the Crisis: Why Strong Planning Systems Are Key to Public Health Preparedness

-

News

Village Head Extols Health Delivery Officers for Bringing Vaccines to the Last Mile

-

Report

GDHF REPORT : How eHealth Africa Advanced Scalable Digital Health at GDHF 2025

-

News

After Losing a Child to Diphtheria, Kano Woman Champions HPV Vaccination

-

News

Kano Communities Avert Painful Cancer Deaths Through Informed Vaccination

-

Press Release

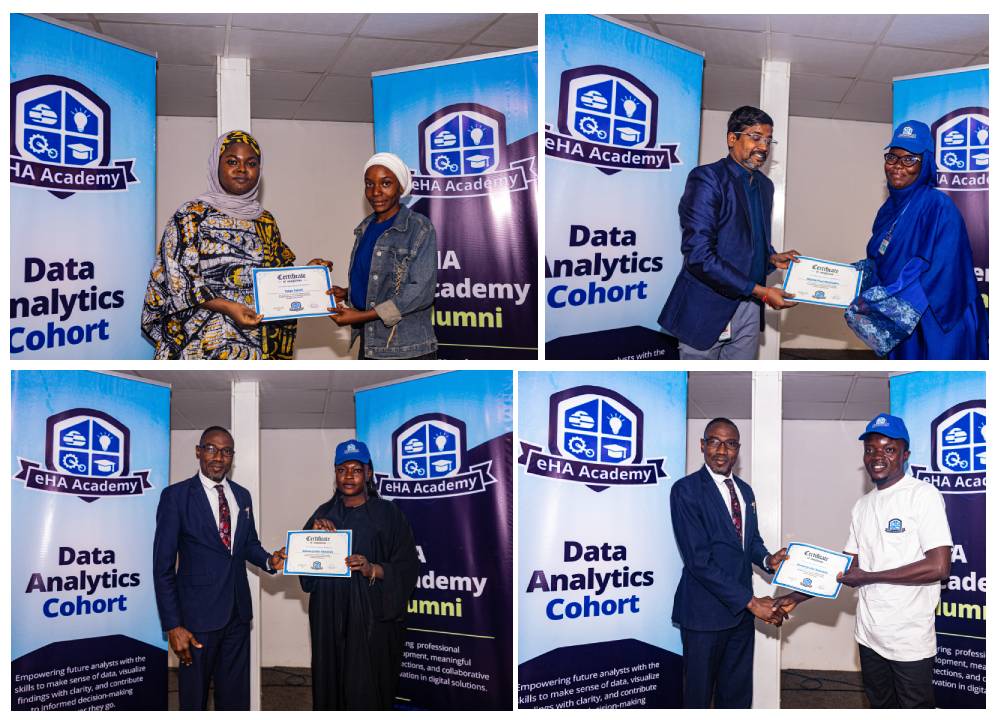

eHA Academy Strengthens the Digital Space with 92 New Graduates in Data Analytics and Advanced JavaScript

-

Press Release

GDHF 2025 : eHealth Africa, Partners Call for Sustainable Financing, Collaborative Innovation for Promote Adolescent Behavioral Change

-

News

How eHealth Africa is Expanding PlanFeld Deployment to Boost Vaccination Reach in Nigeria

-

News

BISKIT : Saving Lives with Smart Blood Information System